- Details

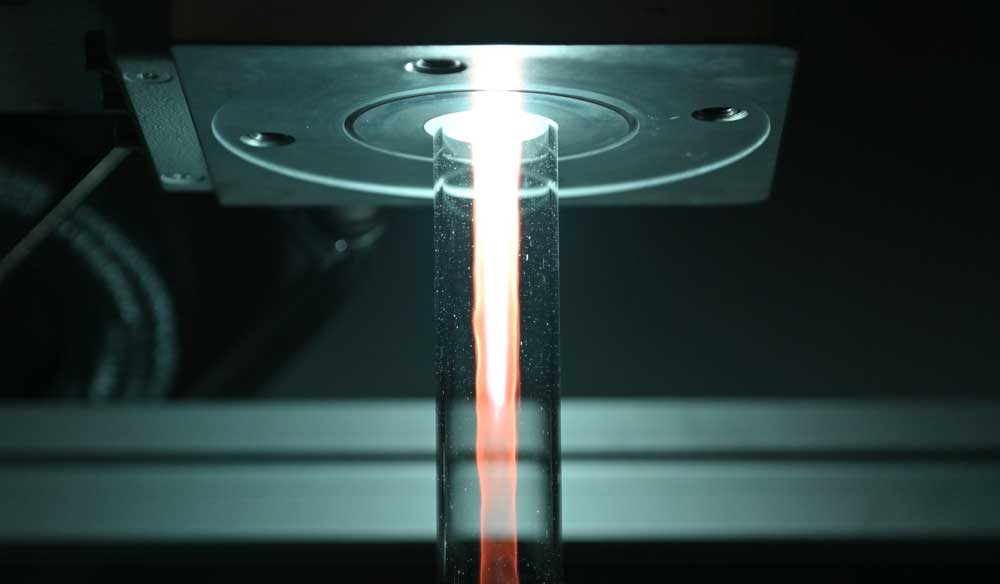

Plasma Science for the 21st century - CRC1316 presents its goal to the National Teachers Congress

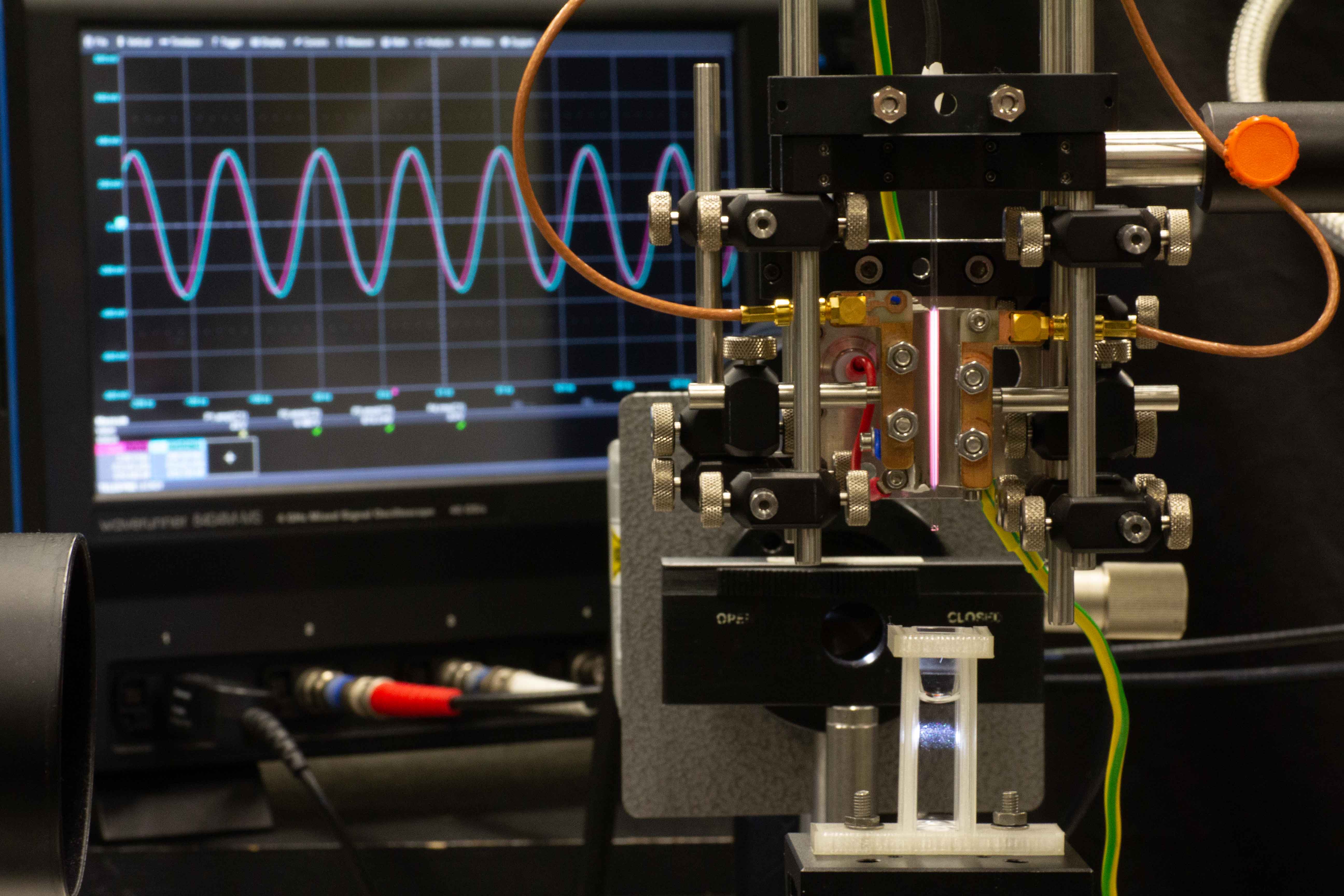

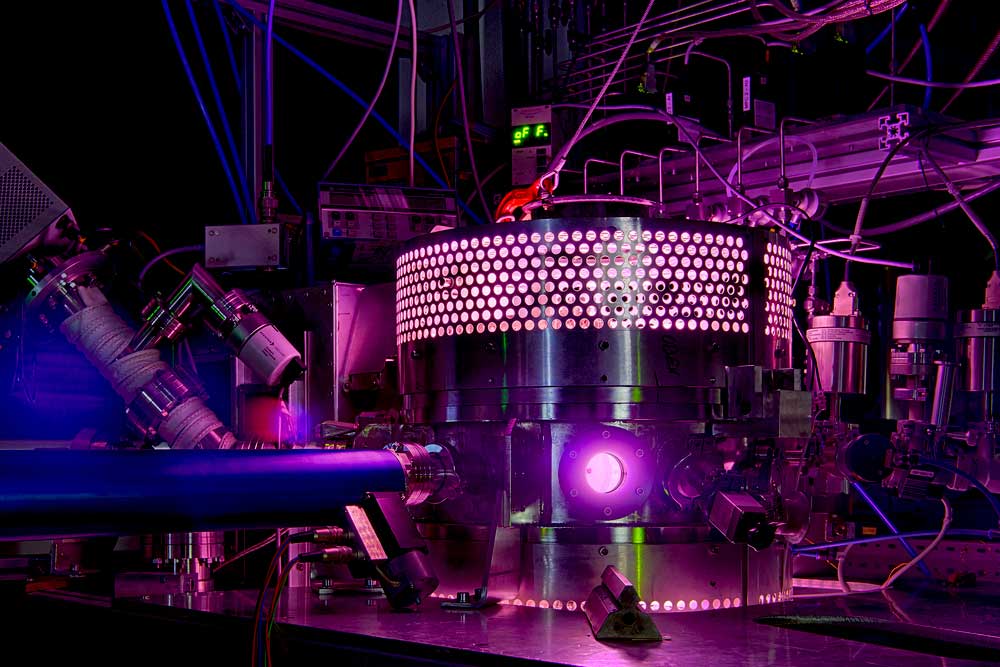

The 115th MNU congress took place in Bochum 1st-4th of May 2025. Judith Golda and Achim von Keudell presented a lecture on plasma science of the CRC1316 in combination with a few experiments from the plasma truck portfolio. A large audience was impressed and inspired by the enormous range of applications of plasmas.

- Details

Public lecture „Licht aus Dunkler Materie “

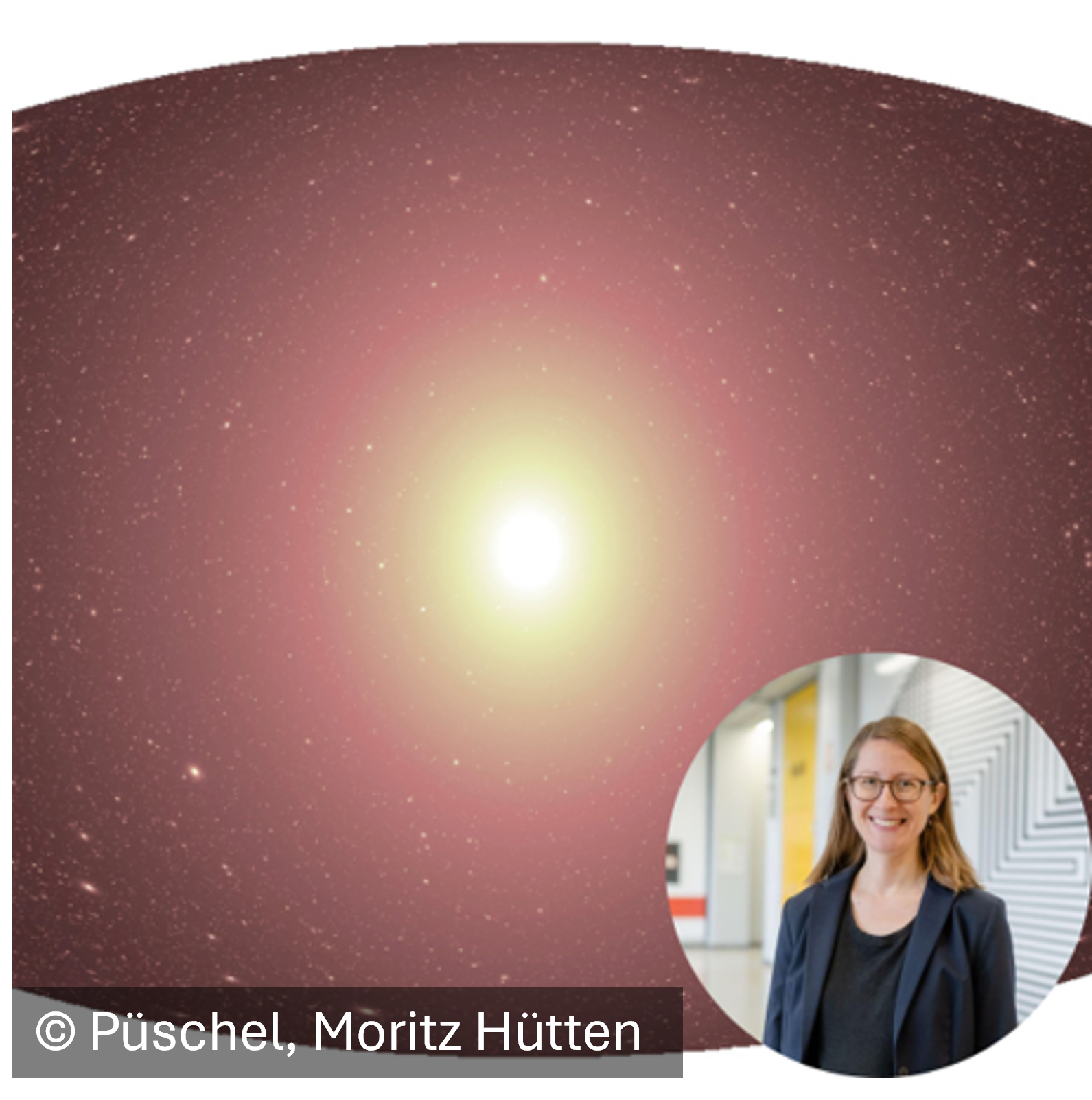

We are pleased to invite you to the public lecture “Licht aus Dunkler Materie " (in German).

Elisa Pueschel will present exciting new results and perspectives in the search for the mysterious Dark Matter, and show how her ‘Dark100’ project is breaking new ground with innovative approaches to uncovering this elusive form of matter.

When 30.4.25 at 20:00

Where Planetarium Bochum

For registration and further information, please have a look at the Planetarium’s homepage.

Picture:

A possible sky map if Dark Matter indirectly produces radiation through rare interactions.

- Details

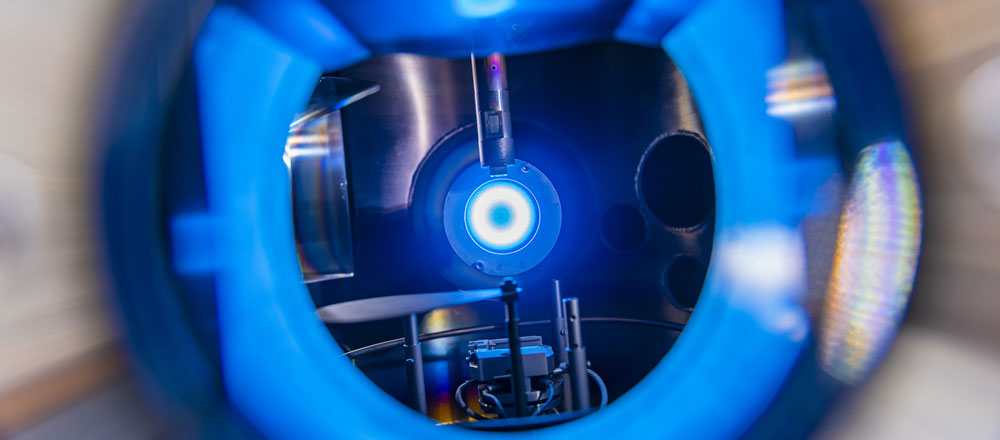

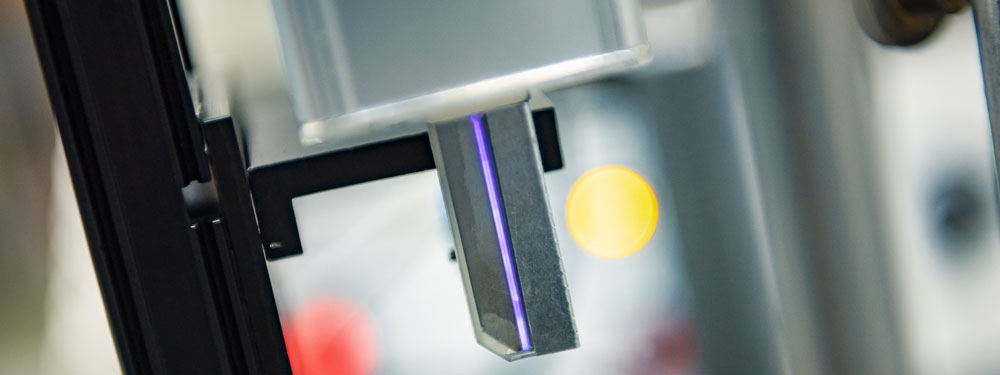

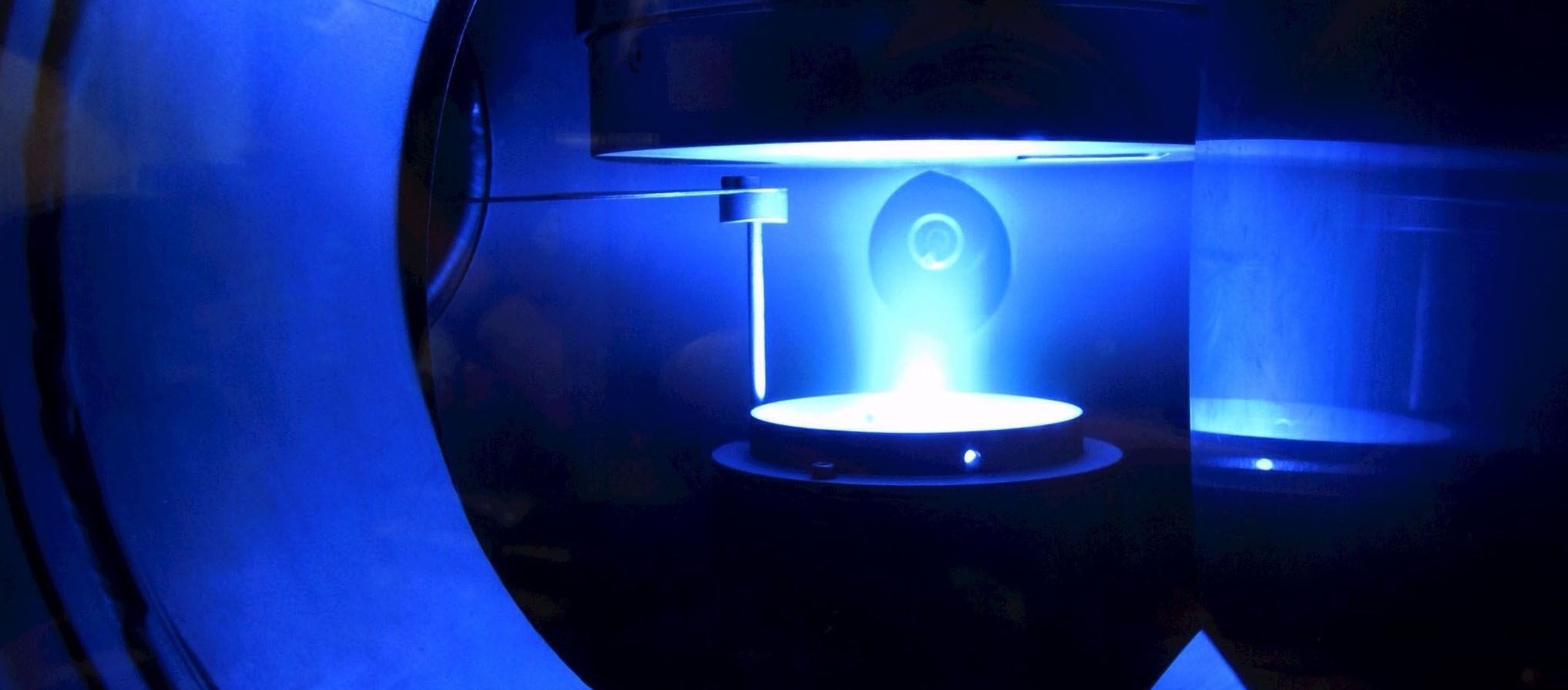

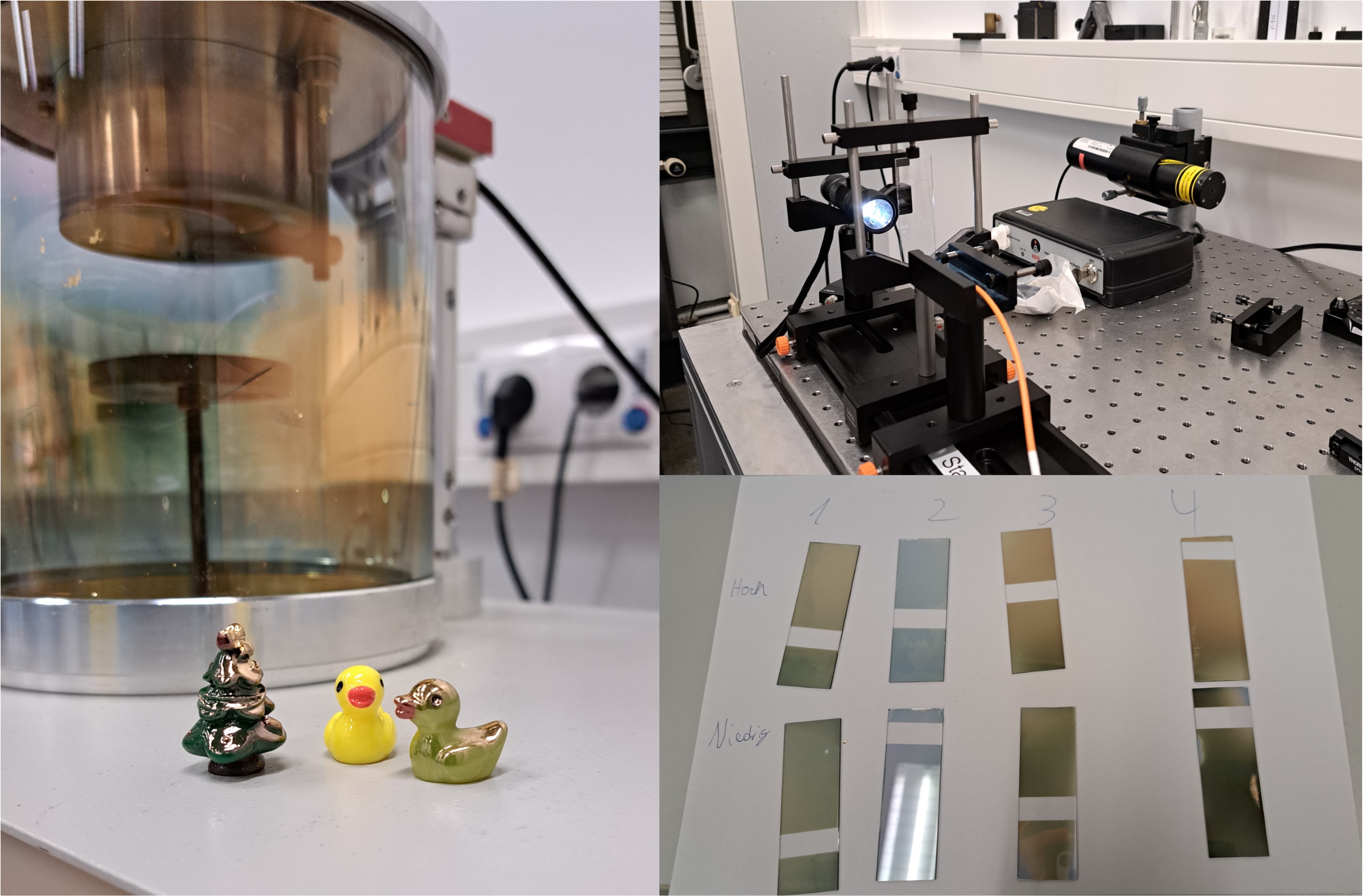

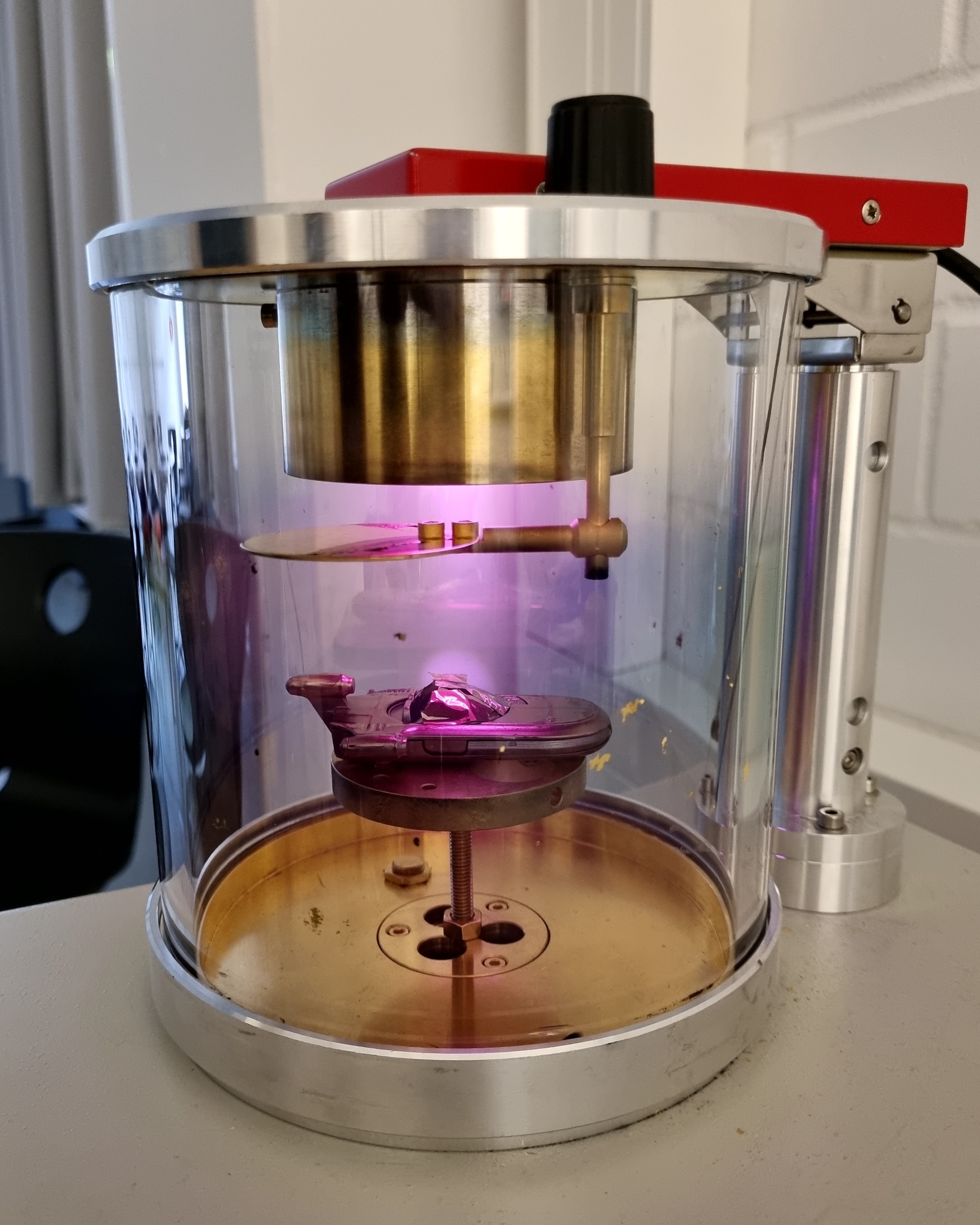

High school student interns at EP2

From 9th to 11th April, two high school students were guests at the Chair of Experimental Plasma Physics. They experimented with the sputter coater, gained insight into current plasma research at the Ruhr-Universität and observed scientists at work.

From 9th to 11th April, two high school students were guests at the Chair of Experimental Plasma Physics. They experimented with the sputter coater, gained insight into current plasma research at the Ruhr-Universität and observed scientists at work.

- Details

Research stay at CSIRO Perth

As part of his PhD project, Sam Taziaux spent two months at the renowned CSIRO Institute in Perth, Australia. There he worked closely with George Heald, head of the SKAO headquarters in Perth, and Alec Thomson, both internationally recognised experts in the field of radio astronomy and the analysis of magnetic fields.

Sam's research project, which is part of A2, is dedicated to analysing cosmic ray transport and magnetic fields in dwarf galaxies. At CSIRO, he was able to benefit from the exceptional expertise there and was able to significantly improve the data reduction and analysis of his observed ATCA and MeerKAT data.

The stay was not only a great professional enhancement for Sam, but also a significant milestone in his scientific career, as he was able to get to know and work with the people from the CSIRO and SKAO. He was also able to establish contacts with the scientist at Curtin University in Perth to exchange ideas and expand his network.

Such research stays are excellent opportunities enabled by the CRC to specifically promote international cooperation. The CRC has thus opened up a unique opportunity to become involved in a global scientific network at an early stage, an invaluable advantage on the path to scientific independence.

Picture: Sam Taziaux and his supervisor Ralf-Jürgen Dettmar at the SKAO regional center at CSIRO, Perth.

- Details

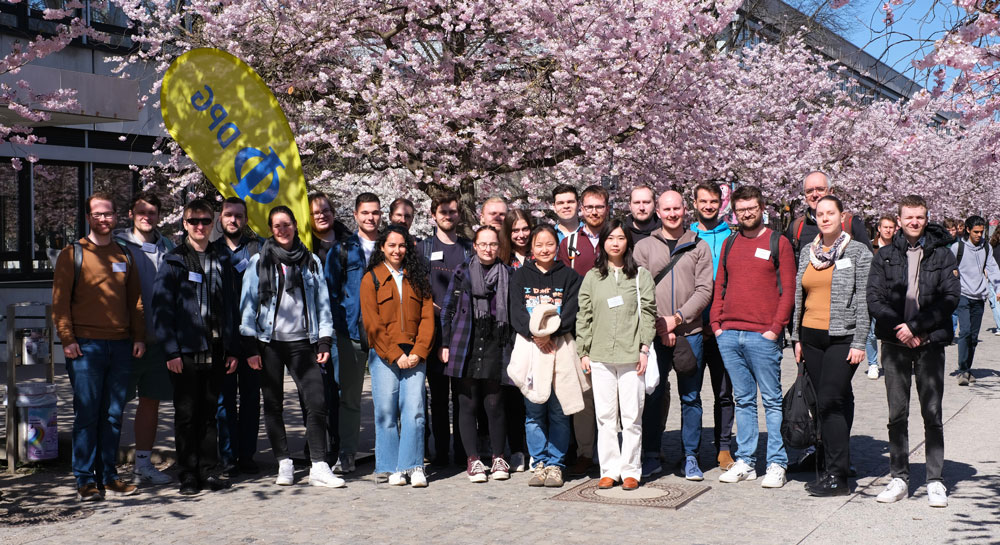

DPG Göttingen 2025

From March 31 to April 4, 2025, the spring conference of the German Physical Society (DPG), Matter and Cosmos Section, took place in Göttingen.

The SFB 1316 participated in the spring conference with three invited lectures, numerous presentations, and poster presentations. With these contributions, we not only presented the research work of the SFB 1316, but also sought to engage in active exchange with researchers in order to strengthen the network and good cooperation.

- Details

Announcement for the 4th Workshop on FAIR Data in Plasma Science

We are happy to announce the 4th Workshop on FAIR Data in Plasma Science (FDPS-IV), which will take place online and in-person on

12-13 May, 2025 at the Leibniz Institute for Plasma Science and Technology (INP) in Greifswald, Germany.

This workshop is intended to provide an overview of successful solutions for collaborative research data management with the goal to make data findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable (FAIR). It is a continuation of annual events on research data management in the low-temperature plasma (LTP) community in the past years. Open for everyone, the FDPS-IV workshop provides insights into best practice in day-to-day research work as well as infrastructure tools for handling of research data. To even broaden the discussion on future applications, a poster session will be held in-person.

Call for poster contributions

Researchers, data managers, and practitioners are invited to contribute to the discussion with a poster on their solutions on research data management. Submissions that highlight real-world experiences, best practices, and insights related to the integration of FAIR principles into research workflows are encouraged.

Registration

The workshop will be held as a hybrid meeting and participation is free of charge. Please save the date and register by following the registration link on the workshop website: https://www.plasma-mds.org/ws-fair-data-plasma-science-4.html.

Poster contributions must be submitted during the registration process. Please note that the attendance in person at INP and the number of poster spaces is limited, so early registration is encouraged to secure your spot (max. DIN A0, portrait format).

The registration will be closed on 4th May, 2025.

Contact

The workshop organization is part of the activities of the working group Experimental Plasma Physics at the Kiel University (CAU), the INF project of the CRC 1316 at the Ruhr-University Bochum (RUB) and of the department Plasma Modelling and Data Science at Leibniz Institute for Plasma Science and Technology (INP).

Dr. Markus Becker

Leibniz Institute for Plasma Science and Technology (INP)

Felix-Hausdorff-Str. 2

17489 Greifswald

Germany

E-mail:

- Details

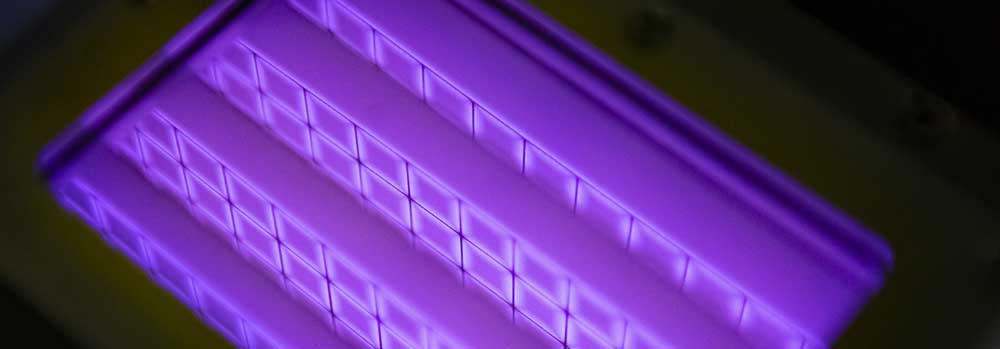

The student's project week during the fall vacations

The student's project week during the fall vacations

The project week at the Ruhr University Bochum took place again this autumn break. Students could choose from three workshops. In the workshop 'From Plasma to Gold Layer', they learned exciting facts about the properties and diverse applications of plasmas. The students used the sputter coater to create thin layers of gold and examined the coatings. They investigated the best way to deposit the layers and presented their research in a poster session. The project week also provided an opportunity to learn about the working environment of scientists and current research projects and to get a taste of university life.

- Details

Luminous plasmas were ignited at MINTsight.BOchum

On 18th February the MINTsight.BOchum, a study orientation day took place. High school students attended a lecture, were guided through laboratories, and could participate in exciting workshops. In our plasma workshop, students gained hands-on experience with these fascinating gases and gained insight into studying electrical engineering and physics, as well as plasma research at the Ruhr University Bochum.

- Details

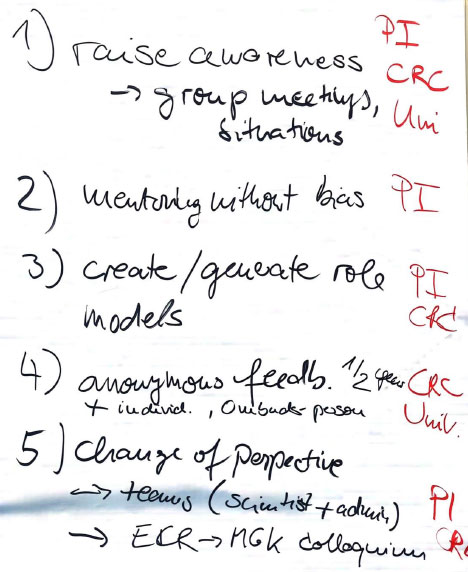

Unconcious Bias

On Tuesday, March 4, 2025, members of the SFB 1316 participated in a workshop on the topic of Unconscious Bias led by Dr. Juliane Handschuh. The workshop's objective was to understand the impact of prejudices in scientific research and general work environments and learn to recognize unconscious biases in oneself and in the workplace. After Dr. Handschuh gave an introductory talk on the topic, the group was divided into groups of Early Career Researchers (ECRs) and Principal Investigators (PIs) to encourage an open exchange. In preparation for the workshop, participants had been encouraged to anonymously submit personal incidents where they experienced a bias. The group exercises were used as case studies and foundation for discussion. Together, strategies to recognize and adequately approach unconscious biases were developed as a directly affected person and as a bystander. At the end of the workshop, both groups joined again for a final discussion. The workshop provided valuable insights into the complex topic of unconscious biases and has provided the members of the SFB with practical tools to foster a more inclusive research environment.

On Tuesday, March 4, 2025, members of the SFB 1316 participated in a workshop on the topic of Unconscious Bias led by Dr. Juliane Handschuh. The workshop's objective was to understand the impact of prejudices in scientific research and general work environments and learn to recognize unconscious biases in oneself and in the workplace. After Dr. Handschuh gave an introductory talk on the topic, the group was divided into groups of Early Career Researchers (ECRs) and Principal Investigators (PIs) to encourage an open exchange. In preparation for the workshop, participants had been encouraged to anonymously submit personal incidents where they experienced a bias. The group exercises were used as case studies and foundation for discussion. Together, strategies to recognize and adequately approach unconscious biases were developed as a directly affected person and as a bystander. At the end of the workshop, both groups joined again for a final discussion. The workshop provided valuable insights into the complex topic of unconscious biases and has provided the members of the SFB with practical tools to foster a more inclusive research environment.

- Details

Welcome to our new PI Chris Riseley!

We are excited to announce that Dr. Christopher Riseley has been appointed as a new PI at our CRC.

Chris is a Junior Professor of Radio Astronomy at the Astronomical Institute of Ruhr-University Bochum (AIRUB). His research focuses on using radio telescopes worldwide to study clusters of galaxies. He aims to answer key scientific questions related to diffuse radio sources in galaxy clusters, including canonical relics, haloes, and mini-haloes. Chris is also exploring the unique sources discovered by the precursor instruments for the Square Kilometre Array (SKA).

Specializing in long-wavelength radio astronomy, Chris works extensively with data from the LOw-Frequency ARray (LOFAR), the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA), the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), and the MeerKAT telescope in South Africa.

In the coming years Chris will use these instruments to explore galaxy groups, understanding the interplay between galaxies and their environments. Within the CRC, Chris will apply his radio astronomy expertise to studying the rich physics of dwarf galaxies and nearby galaxies in these environments, answering questions related to dark matter, Cosmic Rays, galaxy evolution, and feedback mechanisms.

- Details

General Assembly 2025

For two days in February, all SFB1491 researchers came together at TU Dortmund to discuss the latest results, covering a wide range of topics including the search for dark matter, investigating (cosmic) magnetic fields, the modeling of accretion and ejection phenomena in astrophysics, and the exploration of cosmic rays and neutrinos in astrophysical as well as collider experiments.

A special highlight were the keynote talks by Dr. Imre Bartos (University of Florida) on "The Expanding Gravitational Wave Horizon: Emerging Opportunities for Multimessenger Discovery" and Dr. Daniel Verscharen (Mullard Space Science Laboratory) on "Electron heat flux in structured plasmas: collisions, trapping, and wave-particle interactions".

More information on our meeting, in particular the program, can be found here