Sciencific magazine of RUB asks for definition of a body

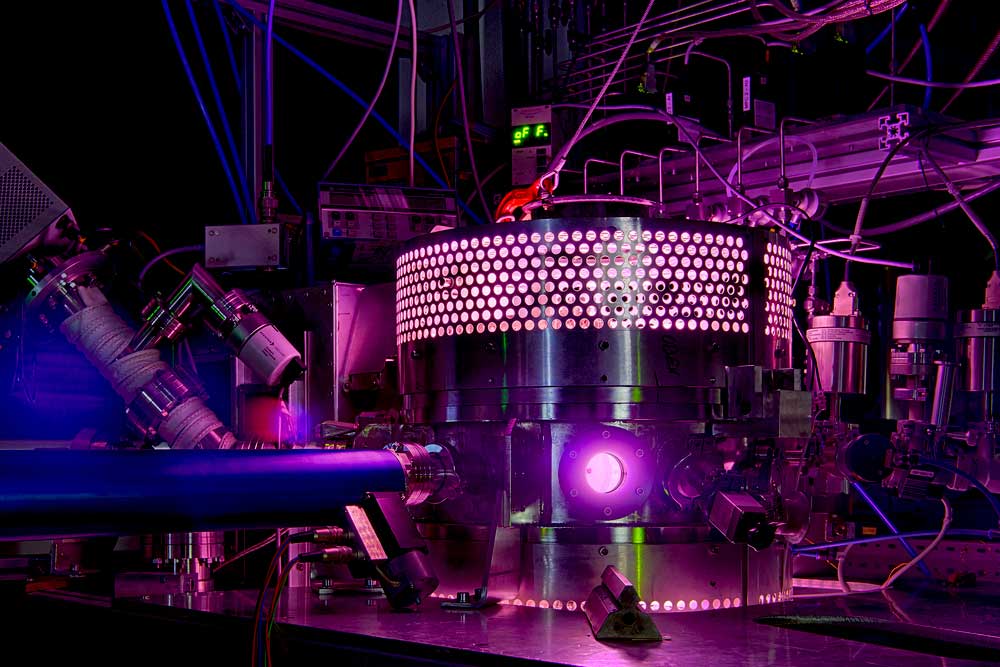

The scientific magazine of the Ruhr-University Bochum had a series of interview concerning the definition of a body within its last edition. Two members of the Reserach Department Plasmas with Complex Interactions gave their opinion about this topic.

Astronomy

As an astronomer, I associate the term "body" most closely with celestial bodies. This is generally associated with objects that Kant defined in 1755 as "... round masses, thus of the simplest formation that a body whose origin is sought can only always have". At that time these were - in extension of "sun, moon and stars" - mainly the classical planets. But actually, I am fascinated by other celestial bodies at the moment, which do not always correspond to the idea of a "round mass" and of which smaller specimens can even be picked up: meteorites. The shape can look like a wrinkled, dried-up potato. The smooth, uniform outer layer hardly shows the important inside. One may wonder how the objects of our planetary system could have developed from these four billion year old lumps. The RUB Mineralogical Collection contains some interesting examples of these small celestial bodies.

Prof. Dr. Ralf-Jürgen Dettmar

Physics

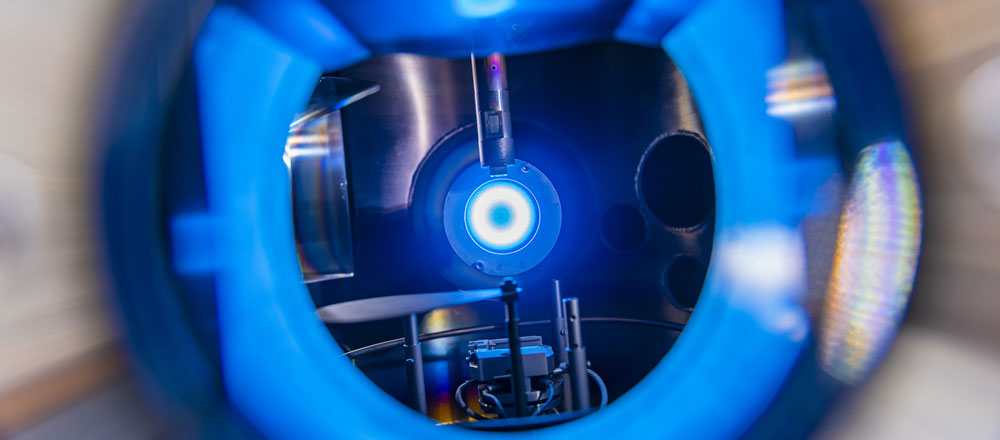

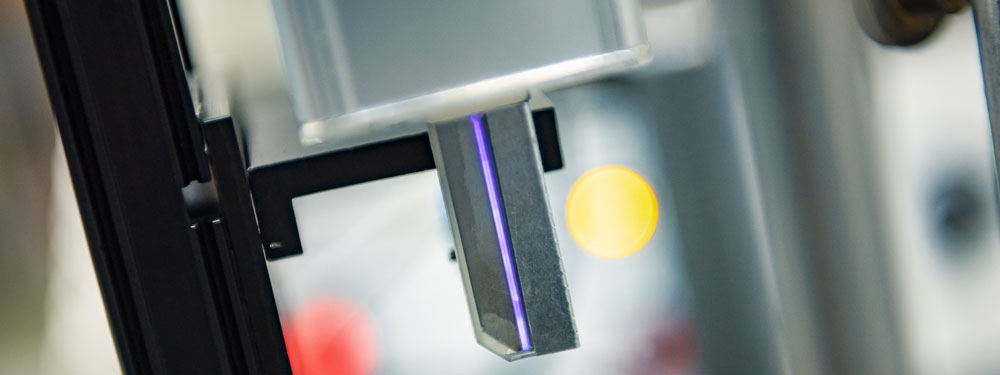

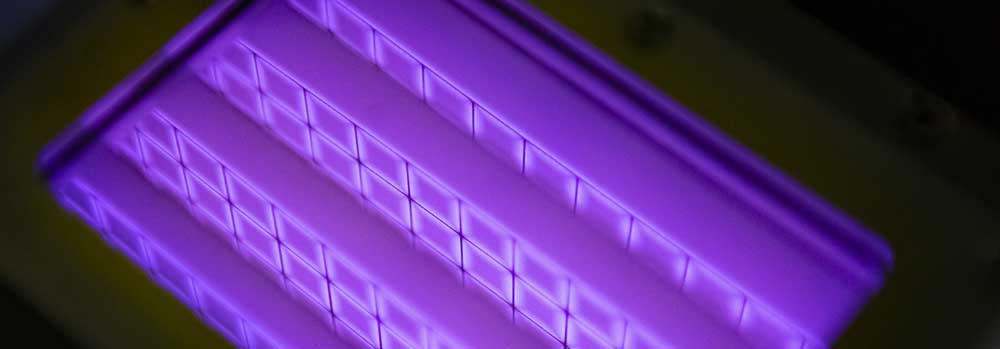

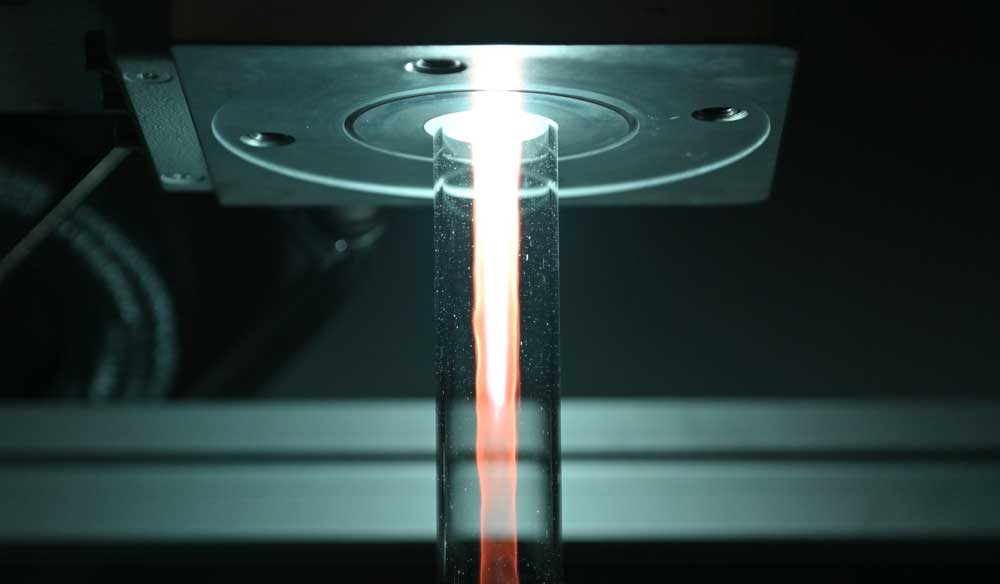

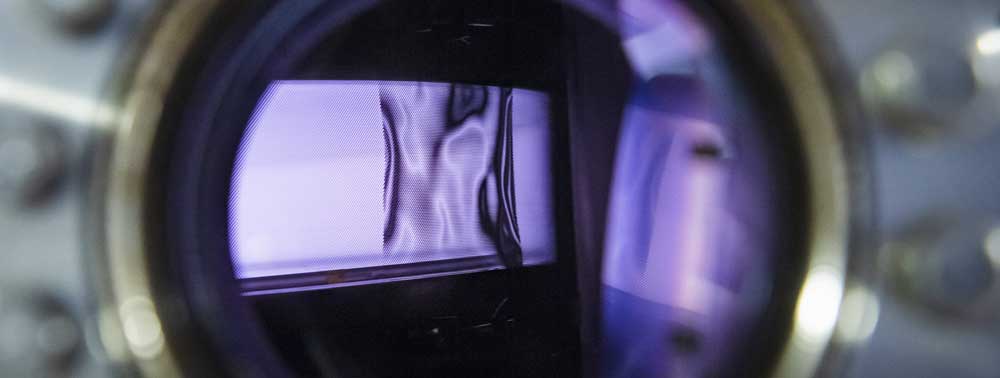

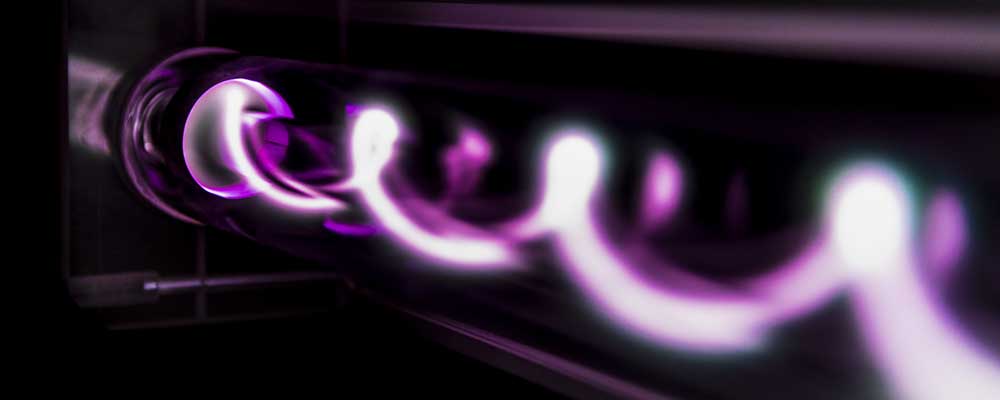

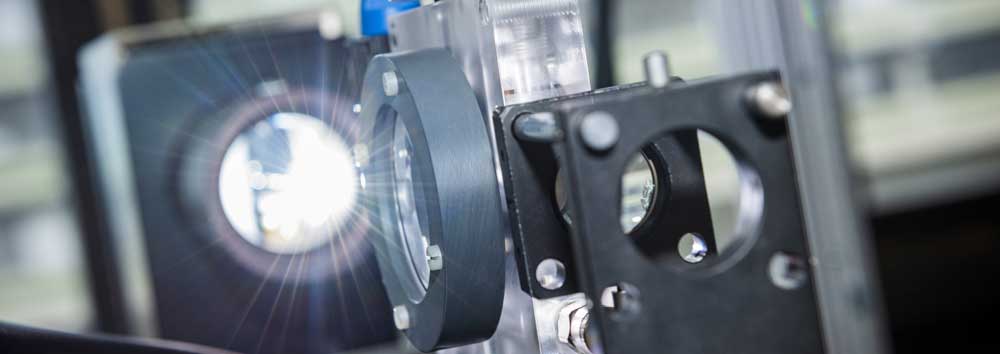

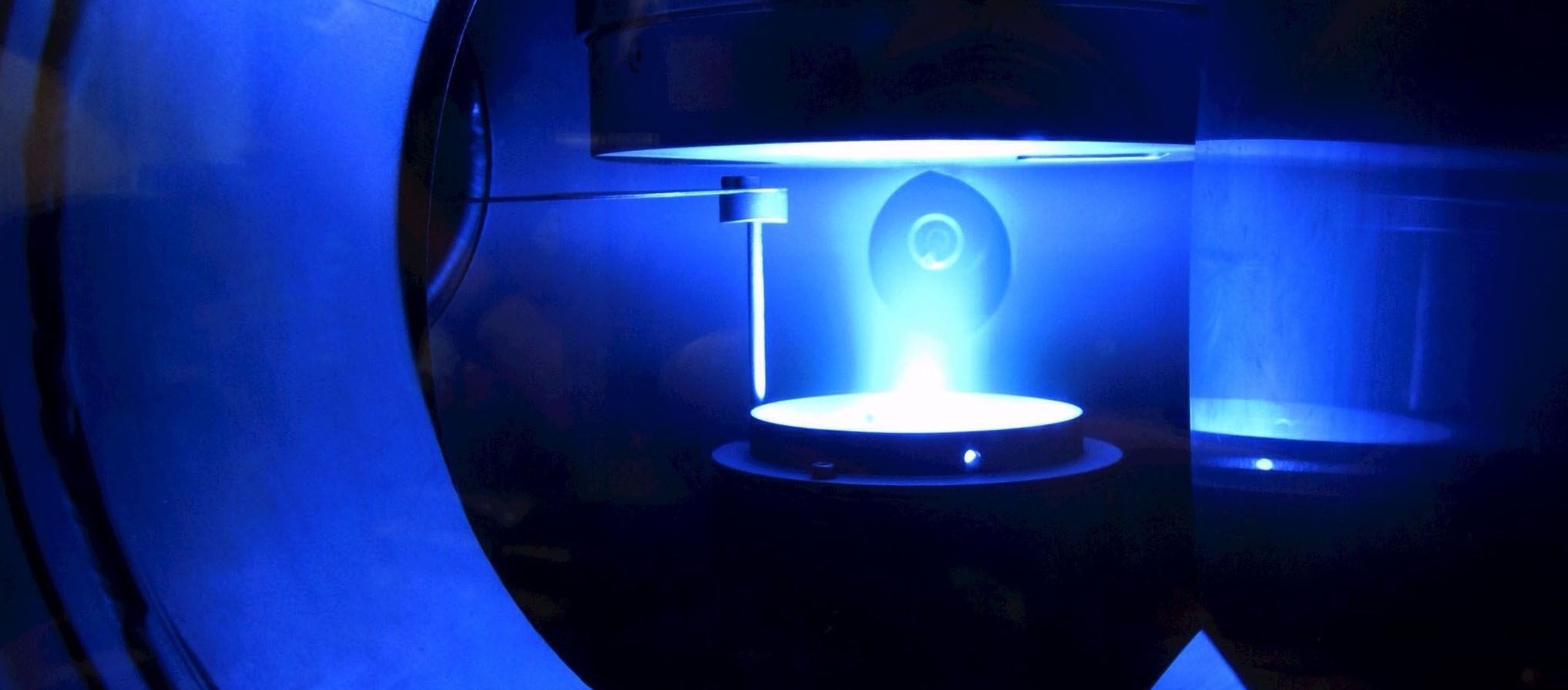

What is a body? The question is wrongly posed from the perspective of physics. In everyday life we take the bodies in our environment through our senses. There is an interaction of particles with this body, which provides us with information about its spatial extension: be it the light particles when we see or the atoms on the surface of our hand when we touch it. The kind of interaction determines the extension of a body, which is investigated in atomic and nuclear physics in scattering expe- rents. This is done by bombarding atoms or atomic nuclei with certain particles and measuring their deflection and energy loss. Electrons, protons, neutrons or light particles are used as projectiles - and depending on the type of projectile and its energy, the results vary considerably. With neutrons, only the atomic nucleus is visible, with electrons and light particles rather the atomic shell. Thus the question of the size of an atom or atomic nucleus has many answers. This interaction is also important on a large scale. For example, the size of a black hole is defined more by the limit of the interaction of light with gravity than by the spatial extension of the heavy celestial body in its interior.

These types of interaction determine how we deal with bodies in everyday life. Thus, holding this ruby booklet with your hands is, in a sense, the interaction of the atoms of your hand with the cellulose of the paper from which this booklet is made. One of the most important laws of quantum physics, the Pauli prohibition, determines that the atoms of your hands cannot easily penetrate those of the paper. Therefore, the notebook lies stable in your hands and you can perceive this body in its size.

Prof. Dr. Achim von Keudell